Description

Classifications of the planktonic algae vary enormously among authors. Diatoms are often treated as either a phylum of their own (e.g. 'Bacillariophyta', Round 1981), or as members of phylum or a division ['Chromophyta' of Hasle and Syvertsen (1996); 'Chrysophycophyta' of Bold and Wynne (1978)]. Divisions within the diatoms also vary, the order here called 'Biddulphiales' (Hasle and Syvertsen 1996) is frequently called 'Centrales', and referred to informally as as 'centric diatoms'.

Synonymy- When this diatom first was discovered in British waters, it was identified as C. nobilis, a diatom first described fron the Java Sea (Boalch and Harbour 1977; Robinson et al. 1980). 'C. nobilis' was also reported from Chesapeake Bay by Griffith (1961). This could also have been C. wailesi.

Taxonomy

| Kingdom | Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protista | Bacillariophyta | Bacillariophyceae | Biddulphiales | Coscinodiscaeae | Coscinodiscus |

Synonyms

Invasion History

Chesapeake Bay Status

| First Record | Population | Range | Introduction | Residency | Source Region | Native Region | Vectors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Established | Stable | Introduced | Regular Resident | Amphi-Pacific | Amphi-Pacific | Shipping(Ballast Water) |

History of Spread

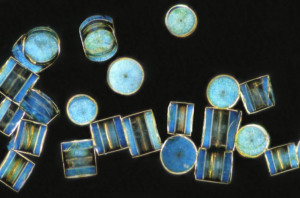

The diatom Coscinodiscus wailesii was described from Puget Sound WA and Departure Bay, British Columbia, where it was described as 'very abundant' in August 1928 (Gran and Angst 1931). Cupp (1943) found it 'not uncommon off southern California'. It is abundant in the Seto Inland Sea off Japan (Manabe and Ishio 1991), and is common in subtropical sediments across the Pacific (Guillard and Kilham 1977), and has been found in Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand, and the Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica (Rince and Paulmier 1986). Hasle and Syvertsen (1997) summarize its distribution as 'warmwater to temperate (recently introduced to North Atlantic waters)'.

The earliest records for Coscinodiscus wailesii in the Atlantic Ocean are for Chesapeake Bay in 1961 [Griffith 1961 (as C. nobilis); Mulford 1962; Mulford 1963; Patten et al. 1963]. It is found in the lower Bay, and along the continental shelf between Cape Charles VA and Cape May NJ (Mahoney and Steimle 1980; Marshall and Cohn 1987a), in the New York Bight (Marshall and Cohn 1987b), and was present in small numbers as far north as the Gulf of Maine (Mahoney and Steimle 1980). In 1978, a 'bloom' of C. wailesii is believed to created large quantities of mucus, fouling fishing gear in the Atlantic off the Delmarva Peninsula. It has been in Narragansett Bay RI for at least 15 years, and is abundant on Georges Bank (Hargraves 1998). This diatom was absent from a number of other phytoplankton studies for the Atlantic Coast of the United States, including that of Hustedt (1955) and Marshall (1971) for the coast of the southeastern United States. In many early studies, Coscinodiscus spp. were not identified to species. While C. wailesii is a well-defined species, the variation of taxonomic skills of different workers is a source of uncertainty (Hargraves 1998). Its distribution south of Chesapeake Bay is unclear, but it has been collected in the Indian River Lagoon, FL (Hargraves 2002), and on the coast of Brazil (Fernandes and .Zehnder-Alves 2002)

The invasion of C. wailesii into European coastal waters is better documented, since phytoplankton have been studied in these waters since before the beginning of the 20th century. Coscinodiscus wailesii (initially called C. nobilis) was first found off Plymouth, England, in 1977, where it interfered with trawling by producing vast quantities of mucus which clogged fishing trawls (Boalch and Harbour 1977). Preserved samples from a long-term sampling program (1948-1976) in the English Channel did not contain this diatom. From 1977 to 1978, the diatom apparently spread from the Atlantic southeast of the mouth of the English Channel northward into the Irish Sea (Robinson et al. 1980). In the 1980's, C. wailesii was found on the French side of the English Channel and the North Sea coasts of the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark (Rince and Paulmier 1986). In 1988-1991, it was found throughout the North Sea, at some locations comprising more than 90% of the phytoplankton biomass (Rick and Durselen 1995).

Chesapeake Bay records of C. wailesii are summarized below:

Adjacent Atlantic Waters - Coscinodiscus wailesii was collected at stations ~40-120 km east of the Bay mouth in April and September-December 1961 (Mulford 1963). In April 1978, fisherman in the coastal Atlantic Ocean between Cape Charles VA and Cape Henlopen DE found their nets coated with slime, making handling difficult. Samples of this slime contained cells of C. wailesii. Concentrations of C. wailesii cells in surrounding waters ranged from 6 to 470 cells/liter (Mahoney and Steimle 1980). In 1979-1981 surveys, C. wailesii was found in near-shore (within 35 km) and far-shore stations (85-130 km offshore) between Cape Henry VA and Cape May NJ (Marshall and Cohn 1987a). In 1980, present in Chesapeake Bay plume and adjacent Continental shelf waters (Marshall 1982).

Lower Bay - In a sampling program run between January 1960, and December 1961, C. wailesii was collected in the lower York River, from the mouth to 14 miles (23 km) upstream (Mulford 1962; Mulford 1963). Griffith (1961) listed C. nobilis, which could refer to C. wailesii, but gave no location.

History References - Boalch and Harbour 1977; Cupp 1943; Gran and Angst 1931; Griffith 1961; Guillard and Kilham 1977; Hasle and Syvertsen 1997; Hargraves 1998; Hustedt 1955; Mahoney and Steimle 1980; Manabe and Ishio 1991; Marshall 1971; Marshall 1982; Marshall and Cohn 1987a; Mulford 1963a; Mulford 1963b; Patten et al. 1963; Rick and Durselen 1995; Rince and Paulmier 1986; Robinson et al. 1980

Invasion Comments

Vector(s) of Introduction - Ballast water seems the likeliest vector for introduction of C. wailesii into Atlantic waters. Large drum-shaped 'Coscinodiscus-like' diatoms are commonly seen in ballast water samples (Hallegraeff and Bolch 1994; Kelly 1993; Ruiz et al. unpublished). Rince and Paulmier (1986) suggest that the species may have been transported by shipping (presumably in ballast water) from the Pacific through the Panama Canal to the Atlantic coast of the United States, and then was carried to Europe by the Gulf Stream. Alternatively, they suggest transplants of Crassostrea gigas (Pacific Oyster) as a vector.

Invasion Status - Coscinodiscus wailesii and Odontella sinensis- seem to have appeared in several well-studied areas in the northwest Atlantic, including Narragansett Bay, Chesapeake Bay, and the Gulf of Maine, since World War II. However, accuracy of identification by different workers is a source of uncertainty (Hargraves personal communication 1998; Mahoney and Steimle 1978).

Ecology

Environmental Tolerances

| For Survival | For Reproduction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Temperature (ºC) | 1.0 | 32.0 | ||

| Salinity (‰) | 10.0 | 38.5 | ||

| Oxygen | ||||

| pH | ||||

| Salinity Range | meso-eu |

Age and Growth

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Adult Size (mm) | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Typical Adult Size (mm) | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Maximum Adult Size (mm) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Maximum Longevity (yrs) | ||

| Typical Longevity (yrs |

Reproduction

| Start | Peak | End | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Season | |||

| Typical Number of Young Per Reproductive Event |

|||

| Sexuality Mode(s) | |||

| Mode(s) of Asexual Reproduction |

|||

| Fertilization Type(s) | |||

| More than One Reproduction Event per Year |

|||

| Reproductive Startegy | |||

| Egg/Seed Form |

Impacts

Economic Impacts in Chesapeake Bay

Coscinodiscus wailesii appears to normally be a small component of the phytoplankton community in Chesapeake Bay and the adjacent Atlantic waters (Marshall and Cohn 1987a; Patten et al. 1963).

Fisheries- In April 1978, in the Atlantic between Cape Charles VA and Cape Henlopen DE, elevated concentrations of this diatom were associated with accumulations of mucus on fishing nets and pots [the latter used in fisheries for Geryon quinquedens (Red Crab) and Centropristes striatus (Black Sea Bass)], clogging them and fouling decks and catches (Mahoney and Steimle 1980).

References - Mahoney and Steimle 1980; Marshall and Cohn 1987a; Patten et al. 1963

Economic Impacts Outside of Chesapeake Bay

The invasion of Coscinodiscus wailesii in European coastal waters was marked by problems with fishing trawls fouled and clogged by the large quantities of mucus secreted by sinking masses of this diatom (Boalch and Harbour 1977; Rince and Paulmier 1986; Rick and Durselen 1995). A similar event, probably due to C. wailesii, was reported off the Atlantic Coast of the Delmarva Pensinsula (Mahoney and Steimle 1980). In Japanese coastal waters, blooms of C. wailesii can interfere with fisheries by massive biodeposition, creating anoxia (Manabe and Ishio 1991). This species can also affect Poprhyra spp. (Nori) seaweed cultures, through shading, fouling, and nutrient competition (Nagai et al. 1991).

References - Boalch and Harbour 1977; Mahoney and Steimle 1980; Manabe and Ishio 1991; Nagai et al. 1991; Rince and Paulmier 1986; Rick and Durselen 1995

Ecological Impacts on Chesapeake Native Species

Impacts of the probable invasion of Coscinodiscus wailesii in Chesapeake Bay and the northwest Atlantic have not been studied. There has been one report of a 'bloom' of this species in the Atlantic between Cape Charles VA and Cape Henlopen DE, in 1978 which produced large quanties of mucus, fouling fishing gear. This event apparently did not affect oxygen concentrations in the Mid-Atlantic, unlike blooms of the dinoflagellate Ceratium tripos in the 1970's. Other possible ecological consequences of this bloom have not been studied, (Mahoney and Steimle 1980), but are discussed below.

In European coastal waters, where the invasion of this species is better documented, C. wailesii rapidly became an important component of the phytoplankton community, comprising a significant part of the biomass, and affecting fishing through its copious mucus production (Boalch and Harbour 1977; Rince and Paulmier 1986; Rick and Durselen 1995; Robinson et al. 1980).

Competition - At some times of year, C. wailesii comprised more than 90% of the phytoplankton biomass in the German Bight, and in some locations seems to have replaced the formerly dominant C. concinnus. Possible reasons for this species' success in North Sea Waters include its high tolerance for trace metals, and the inefficient grazing of copepods (Temora longicornis, Calanus helgolandicus) on this large diatom, and the removal of other phytoplankton from the water column by the mucus secreted by sinking cell masses (Manabe and Ishio 1991; Rick and Durselen 1995; Roy et al. 1989).

Habitat Change - One negative impact of C. wailesii blooms observed in the Seto Inland Sea, Japan is that the rapid sedimentation of this large diatom leads to accumulation of organic material on the floors of embayments, resulting in reduced dissolved oxygen. A peculiar consequence of the increasing dominance of this very large diatom in eutrophic areas is that it is accompanied by increased light penetration, since more of the phytoplankton biomass is concentrated in a smaller number of particles (Manabe and Ishio 1991).

Food/Prey - The copepods Temora longicornis and Calanus helgolandicus engage in 'sloppy feeding' on C. wailesii, probably beacuse of the large size of this diatom, breaking cells, and ingesting only a part of the contents (Roy et al. 1990). Rick and Durselen (1995) suggest that this inefficient grazing will lead to reduced feeding on C. wailesii compared to other species. However, Roy et al. (1990) point out that in spite of the waste due to breakage, copepods are likely to gain more from feeding on a few large cells than many small ones.

References - Boalch and Harbour 1977; Manabe and Ishio 1991; Mahoney and Steimle 1980; Rick and Durselen 1995; Rince and Paulmier 1986; Roy et al. 1989

Ecological Impacts on Other Chesapeake Non-Native Species

Impacts of the invasion of Coscinodiscus wailesii on introduced species in Chesapeake Bay have not been studied. The low abundance of this diatom suggests that its interactions with suspension-feeding invertebrates or other phytoplankton would be rare.

References

Boalch, G. T.; Harbour, D. S. (1977) Unusual diatom off the coast of south-west England and its effect on fishing., Nature 269: 687-688Bold, Harold C.; Wynne, Michael J. (1978) Introduction to the Algae: Structure and Reproduction, , Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Pp.

Cupp, Easter E. (1943) Marine plankton diatoms of the west coast of North America, Bulletin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography of the University of California 5: 1-238

Drebes, G. (1977) Sexuality, In: Werner, Dietrich(Eds.) The Biology of Diatoms. , London. Pp. 250-283

Eppley, Richard W.; Sloan, Phillip R. (1966) Growth rates of marine phytoplankton: Correlation with light absorption by cell chlorophyll a, Physiologia Plantarum 19: 47-59

Gran, H. H.; Angst, E. C. (1931) Plankton diatoms of the Puget Sound, Publications of the Puget Sound Biological Station 7: 417-516

Griffith, Ruth E. (1961) Phytoplankton of Chesapeake Bay, Chesapeake Biological Laboratory Contributions 172: 1-79

Guillard, Robert R. L.; Kilham, Peter (1977) The ecology of marine planktonic diatoms., In: Werner, Dietrich.(Eds.) The Biology of Diatoms.. , London. Pp. 372-469

Hallegraeff, G.M.; Bolch, C.J. (1992) Transport of diatom and dinoflagellate resting spores in ships' ballast water: implications for plankton biogeography and aquaculture, Journal of Plankton Research 14: 1067-1084

Hargraves, Paul E. (2002) Diatoms of the Indian River Lagoon, Florida: An annotated account., Florida Scientist 65: 225-244

Hasle, Grethe R.; Syvertsen, Erik E. (1997) Marine diatoms., In: Tomas, Carmelo M.(Eds.) Identifying Marine Diatoms and Dinoflagellates.. , San Diego. Pp. 3-385

Hustedt, Fredrich (1955) Marine littoral diatoms of Beaufort, North Carolina., Duke University Marine Station Bulletin 6: 1-51

Kelly, Janet M. (1993) Ballast water and sediments as mechanisms for unwanted species introductions into Washington State, Journal of Shellfish Research 12: 405-410

Mahoney, John B.; Steimle, Frank W., Jr. (1980) Possible association of fishing gear clogging with a diatom bloom in the Middle Atlantic Bight,, Bulletin of the New Jersey Academy of Science 25: 18-21

Manabe, T.; Ishio, S. (1991) Bloom of Coscinodiscus wailesii and DO deficit of bottom water in Seto Inland Sea, Marine Pollution Bulletin 23: 181-184

Marshall, Harold G. (1971) Composition of phytoplankton off the southeastern coast of the United States, Bulletin of Marine Science 21: 806-825

Marshall, Harold G. (1982) Composition of phytoplankton within the Chesapeake Bay plume and adjacent waters off the Virginia coast, U.S.A., Estuarine, Coastal, and Shelf Science 15: 29-42

Marshall, Harold G. (1991) Seasonal phytoplankton assemblages associated with the Chesapeake Bay plume, Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 107: 105-114

Marshall, Harold G. (1994) Chesapeake Bay Phytoplankton: I. Composition., Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 107: 573-585

Marshall, Harold G.; Cohn, Myra S. (1987) Phytoplankton distribution along the eastern coast of the USA. Part IV. Shelf waters between Cape Henry and Cape May, Journal of Plankton Research 9: 139-149

Marshall, Harold G.; Cohn, Myra S. (1987) Phytoplankton composition of the New York Bight and adjacent waters, Journal of Plankton Research 9: 267-276

Mulford, R. A. (1963) Diatoms from Virginia tidal waters., Virginia Institute of Marine Science Special Scientific Report 30: 1-33

Mulford, Richard A. (1963) Net phytoplankton taken in Virginia tidal waters., Virginia Institute of Marine Science Special Scientific Report 43: 1-22

Nagai, Satoshi; Hori, Yutaka; Manabe, Takehiko; Imai, Ichiro (1995) Morphology and rejuvenation of Coscinodiscus wailesii Gran (Bacillariophyceae) resting cells found in bottom sediments of Harima-Nada Seto inland sea, Japan, Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 61: 179-185

Nagai, Satoshi; Hori, Yutaka; Manabe, Takehiko; Imai, Ichiro (1995) Restoration of cell size by vegetative cell enlargement in Coscinodiscus wailesii (Bacillariophyceae)., Phycologia 34: 533-555

Patten, Bernard C.; Mulford, Richard A.; Warinner, J. Ernest (1963) An annual phytoplankton cycle in the lower Chesapeake Bay, Chesapeake Science 4: 1-20

Rick, H. J.; Durselen, C. D. (1995) Importance and abundance of the recently established species Coscinodiscus wailesii Gran & Angst in the German Bight, Helgolander Meeresuntersuchungen 49: 355-374

Rince, Yves; Paulmier, Gerard (1986) Donnees nouvelles sur la distribution de la diatomee marine Coscinodiscus wailesii Gran & Angst (Bacillariophyceae), Phycologia 25: 73-79

Robinson, G. A.; Budd, T. D.; John, A. W. G.; Reid, P. C. (1980) Coscinodiscus nobilis (Grunow) in continuous plankton records, 1977-78, Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 60: 675-680

Round, F. E. (1981) The Ecology of Algae, , Cambridge. Pp.

Roy, S., Harris, R. P., Poulet, S. A. (1984) Inefficient feeding by Calanus helgolandicus and Temora longicornis on Coscinodiscus wailesii: Quantitative estimation using chlorophyll-type pigments and effects on dissolved free amino acids, Marine Ecology Progress Series 52: 145-153